|

Photo by Dave Adamson via Unsplash Five months. Five glorious incredible months with my 21-year-old son home. This gregarious social butterfly was summoned home at the end of his Miami Spring Break. Hunkered down to resume virtual school work. With few distractions, he earned the best grades of his college career so far.

I couldn't have been happier. I got to see my son months earlier than I had thought, and without an internship that would take him out of the state. We spent a summer together, as he did not socialize nearly as much as normal. No job (UberEats was not worth the risk), but lots of video games, and of course faithful workouts. We talked about so many things - social issues, education, politics, finance, religion, sex. He schooled me on the new spirits and we experimented with mixed libations. Mother and son, but also friends with deep history. We talked of risking your life for those you love, death, joy, advocating for yourself and others. And, I made sure he knew that his life has worth far more than a football player, that he had choices. He can walk away from anything. No judgment, no questions asked. And still, he chose to return to school. He is an adult. I cannot dictate his moves. He must make his own decisions. As his mother, all I can do is love him enough to give him the best knowledge and wisdom I have. And I did. It is his life. I can rest easy knowing that I left it all on the field.

0 Comments

Photo by Hannah Wei via Upslash. The phone rings. It is late. The voice on the other end immediately apologizes for the hour, but there is something else. I hear the pain. Then silence. Then, the news that my friend has lost her mother. That like mine, succumbed to a long bout in the hospital. With her sister now also gone, I was the first call. She knew I would understand.

I did the only thing I knew to do. I cried, too. I helped with logistics, took care of whatever details she would entrust to me. And I did it happily. And wished I could do more. I loved her in ways that I did not know I could - because that is what you do when your friend loses their mother. The feeling of aloneness is vast and easy to get lost in. She would not be lost on my watch. That was years ago, and I figured that this is simply what adulthood is now like. But then, my 21-year-old son got that call last week. In a pandemic. A college friend had lost his cousin unexpectedly. Someone who was as close to him as a brother. Sam described to me the wails of pain that came from his friend. He still remembers. Tomorrow, Sam heads back to his college campus. In a pandemic. Although it is not my choice, what my daughter has taught me (from refusing to move from NYC in a pandemic) is that his childhood home is not his real home anymore. He is an adult, who was on loan to me for a time. He has done everything he needs to do to be healthy, and he needs to finish this last chapter of his life - finishing his senior year of college and two degrees. Right now, his home is in another state. After graduation it will likely be a different state. This is parenting. This is life. I respect his need to care for his friend. I get it. He is me, just a better version. The way he loves is forever. A loyalty that seems more mature than his years. His bond to his friend was already deep, and now it is deepening. Soon it will be in person, despite my misgivings. After all, I think about him maintaining his health constantly. But I also am reminded of every testimony I have. Every one that he has. We have been blessed and delivered from some dire circumstances. I will trust Him now, also. Photo by Nick Fewings via Unsplash. In four more weeks I will be in a building

That will not be disinfected with regularity Not because of staff But funding My colleagues, families, and students will be in our building No masks required The collection of droplets in the air may be lethal for us Especially when you consider how people have been living But there is no consideration We are teachers We serve the children We will just have to fill in the gaps, as usual Take temperatures (And buy thermometers to take temperatures) Disinfect classrooms (And buy cleaning products to disinfect classrooms) (And buy gloves) Wash hands frequently Hmm...where? Only one staff bathroom Kids' bathrooms run out of soap And paper towels Be a team player Social distance But don't make colleagues social distance Or students Be a team player Teach extra kids when colleagues are absent Because there will be no subs And teachers' increased risk is not a concern But we must have school! No school is bad! Because babysitters are a must Not because education is a must I say: Why can't we do all virtual school? They say: What about the businesses? To which I respond: Who will be left to patronize them? Photo by Aaron Burden via Unsplash. I refuse to believe that being concerned for my own safety is selfish. It is not. Being made to feel this way is nothing more than gaslighting. Since when is the overarching concern for human life unnecessary? Why does it have to be balanced?

I am a proud educator of children. I have found success in doing this in person, and recently, and to a lesser extent, through virtual means. Being an educator is part of my identity. It is my passion. However, I do not think my need to educate should supersede children's need to survive. I think that is selfish. The way we have always done it - capitalism and a "booming economy" - this will have to be rethought. We simply can not have schooling used as babysitting while parents work to fuel the economy. That model will not work in a pandemic. Perhaps this, too, is part of what we always knew, but is glaringly obvious now. We must begin to care for each other. We really never have on a large scale. Photo by Robin Benzrihem via Unsplash You came into my space with no mask

Knowing you could infect me Knowing that if I get sick I would die faster Than you Knowing that so many of us have lost loved ones Because someone, no YOU, decided That wearing a mask was Too Much Trouble How nice it must be To treat people as replaceable You have no idea What humans know How humans behave Photo Credit: Anshu A via Unsplash Remember when this question was but an extension of a greeting - something said out of habit? We didn't always really want to know how someone was doing. We were quite content with the expected "Fine." I've asked this question a lot since March 13. Actually, I have asked it constantly. Part of my coping strategy. Friends and family (and even not-friends) ask me all the time. It's nice to be asked. But you know what? It is taking me longer and longer to answer it. Why? Because first of all, I am not fine. And even if I lied and said I was, it would be obvious that I was lying. "How are you" alternatives: Are you physically safe? Are you healthy? Are you in a space for a conversation? Would you like me to just listen? Did you sleep last night? Do you have enough food? Are you going to the protest? Will you social distance? Do you promise to be careful? What time is your curfew? Are you sure you can trust them? Did you pack an emergency travel kit? Can you stay on the phone with me and not talk? Can you send bail money? Will you use your body to protect mine? Will you care for my loved ones if I don't survive? What a difference a day makes. Photo Credit: Mike Von via Unsplash

So we are in a pandemic. Most of the country is on some form of lockdown. Those who can work from home, are. Those who can't risk their own lives to survive, so that the rest of us can. Teachers are expected to continue to teach. Remotely. Assuming they are able - outfitted with technology, stable in their homes with parents who can stay home with them, healthy and with healthy caregivers. The world is expected to continue spinning until...

So, in the midst of trying to cope and establish normalcy, I spend time in emergency remote teaching during the day, fortunate to have stable employment and a safe work environment. My family is healthy. I am in virtual contact with many, and often. I enjoy escape as much as anyone, but am finding it impossible to pull off. I reach for the familiar pursuits. I throw myself into antiracism. There certainly is no shortage of projects, since we are in a heightened state of things. It is a balance of speaking up and telling the truth and fighting feeling that the words are useless. After all, can I really afford the stress physically? Can I afford to expend energy that may need to be stored for literal survival? Is this all there is? Just a count-down until the last day? Do my students feel it? That I am not okay? I am not used to this silence from them. They are way too polite. We are not talking about the thing we are most afraid of. It is not normal. When will it be normal? Would we recognize normal now if it presented itself? Image by Priscilla du Preez via Unsplash I lost another child today.

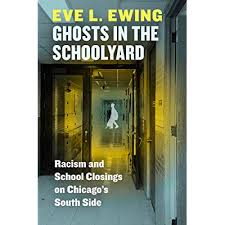

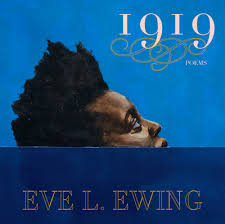

Not my own, not one that I birthed. But another who was stolen from me. I never thought my life as an educator would Make me remember the Middle Passage When reassignment is punishment Much like a child stripped from its mother on African shores Or like seeing each other from different plantations Trying not to get too close And not to look too long For the master would know how much we hurt And we couldn't let them win that way. Because remembering was just too hard The lessons of last year The talks, the smiles, the breakthroughs The hugs, the laughs, the contented silence. We forced ourselves to be ok with this existence Waited until alone for the tears Today came oh too soon No more visiting the plantation down the hall No more daily hellos or sneak hugs. Today was goodbye and snot Father and son and teacher My words trying to make it better when it isn't With overseer overseeing the scene. Are you happy now? Beginning on September 3, Tyrone Martinez-Black, Kelly Wickham Hurst, and I will be moderating a Twitter chat on the book, Ghosts in the Schoolyard written by Eve Ewing. The story of its conception follows, as well as other thoughts on my mind. It all starts with a math conference. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) is having their annual meeting in Chicago in 2020. In fact, this gathering is special, commemorating its centennial. As I attended my first annual meeting in 2019, I kept thinking about the next year's conference and its connections to history. I wondered about the organization's stories and anecdotes of the past. Specifically, I wondered if I would even be welcomed as a member a hundred years ago. I could not imagine I would. Although I had this discussion with other members back in April, these wonderings still populate my thoughts. The concepts of equity, social justice and cultural responsiveness have made it to the fore of our American math world, yet the definitions are far from universal. Also not widely understood is how best to implement culturally responsive pedagogy or teach mathematics with social justice in mind. Yet, these pedagogical moves are not new. How did we get here? Or, how is it that we are still here? Land acknowledgments now occur with more frequency in math spaces than they once did. These are acknowledgments that the lands we inhabit in these gatherings are stolen from indigenous peoples. Sometimes, it is a mere mention of this fact, other times, it is a more elaborate tribute, involving naming the nations in question and/or asking for their blessing. And yet, what seems to occur without much thought is the lack of deliberate place-based consideration that goes beyond a list of tourist attractions. The more history I learn of my own people, and others from groups still marginalized, I am curious about stories of resistance. Did Black mathematicians have to fight to gain membership? How did they do this? What methods were effective? How hard has it been for marginalized mathematicians to make their way? How hard is it still? What I was yearning for is the place history, or as Tyrone has aptly named it, place value. Chicago Place Value With the NCTM centennial event being in Chicago, I couldn't help to be drawn to Ewing's 1919, a book of poetry, written about Red Summer. While researching her book, she stumbled upon a 1922 report that followed the hundreds of deaths during white supremacist attacks in several cities, including Chicago. Red Summer. A hundred years prior. A haunting coincidence. Again I wondered about how my identity as a mathematician would have been realized in that environment.

Eventually, I found myself tweeting about 1919 and wanting to read her other book to learn all I could about Chicago. If we were to inhabit this place, it made sense to me that we honor it by being as knowledgeable as possible about its history, especially its recent history, as it related to education. Tyrone, a Chicagoan tweeted back and offered to read along with me. Kelly, another Chicagoan, chimed in as well, and we found ourselves talking and planning. In no time, we had decided to create a Twitter chat so that all of us, not just those in math education, could benefit from the history that surely we hadn't before known. To truly acknowledge a place, we must value its history, beauty, and struggles. What is it that still hides? Where are the ghosts? I am honored to learn from Tyrone and Kelly, who are making Chicago history. We live in a time when it is difficult to discuss racism openly, let alone its effects. Yet, the history must be faced, and the hard work of change must be done together, in community. We invite you on the journey with us. The following blog post is part of the Virtual Conference on Humanizing Mathematics, hosted by Hema Khodai and Sam Shah. It appears as a conversation with my friend, Hema Khodai. Writing Prompt: How do you highlight that the doing of mathematics is a human endeavor? How do you express your identity as a doer of mathematics to, and share your “why” for doing mathematics with, kids? H: We can’t remember how we first “met” and we certainly didn’t take the time to get to know one another. From the very start, we dove heart-first, with little preamble, into intense conversations about mathematics, the human experience, and the lack of humanity in mathematics education. We were committed to redefining mathematics as a human endeavour for every one of our students before we even met in real life. Our blogpost is a glimpse into a typical Marian-Hema conversation. M: Thank you for these thoughtful questions. I think I would like to begin with the second question about the “why”: specifically why we do math with kids. The most powerful mathematics I have been a part of began with my father. We would “do math” at the kitchen table for hours. Math was magic, math was the best puzzle to solve. But math was (and is) also love. The love that came from him through the math was palpable - not figurative, but material. I could feel it, name it, touch it. So, my why when I first began teaching was to recreate this for children, wanting them to experience what I had. H: My why for the learning and teaching of mathematics hinges on safety, stability, and belonging. At fourteen months, I was a refugee fleeing a war-torn motherland. By the time I was five years old, I was a displaced child seeking a common language to enter and belong in new places and spaces. Math then became something that gave me comfort, I was good at it, I could do it alone, on my own, while my parents worked to ensure our survival and safety, and eventually led to acceptance from teachers and admiration from peers. I built my identity around my ability to do math. M: This really moves me. You speak of math almost as your companion and confidante. I wonder how many students see it that way. I think I want them to see it as relational, but I had not considered that the relationship between themselves and math may not include me at all. You now have me wondering if I have ever given space for that possibility: math as refuge. H: Math as refuge. As a graduate student, completing courses toward a Masters of Mathematics for Teachers, I continue to immerse myself in new learning and find solace in understanding modular arithmetic, resolution in solving Diophantine Equations, and productivity working with Gaussian integers to solve familiar problems. This spring, my professor urged me to continue on, despite the extenuating circumstances of excruciatingly painful losses in my life. It was a reminder of a whole wide mathematical world out there that is unknown to me and awaits my arrival. M: That unknown world. What worries me a lot is that the mathematics of my ancestors, like the languages they may have spoken, is unknown to me, and unknown to the world. How will I ever really know the math that has been denied me? How will my children and students ever know? H: If I truly believe mathematics to be a human endeavour, then I accept that the mathematics of our ancestors is not lost to us. It is there to be reclaimed. M: But how will I know it is mine? I want to know. Need to know. And yet...your mention of belonging has me in my feelings, too...we have talked so much about how some math spaces don’t make us feel as though we belong. What a paradox that the inanimate mathematics signals belonging and community, yet when some humans are added, that same safety can disappear. H: Ooooh. So it is not mathematics in itself that closes doors. It is the self-appointed keepers of the gates that create exclusionary climates in spaces of learning and dictate terms in places of doing. The systems of oppression that are enacted in institutions to dehumanize the experience of mathematics for some. M: Well, are they self-appointed or do we, all of us, give that permission away - to those who think themselves good stewards of knowledge, but who lack the larger body of what truly is mathematics? H: I don’t know if we ever truly gave it away as much as it was wrested away from us and colonized. Like our lands, our bodies, our minds, and our cultures. M: It’s the not-questioning, though. There was a time where I just took the information as given, never questioning its source, and whether or not it was valid. I am on a journey to know... H: I think that’s the journey. That awakening of the critical self that peels away layers of oppression and reveals the network that confirms we each belong with mathematics. Thus also belonging with one another. M: Which brings me to another question: How will we all come to that understanding? You and I have these talks often, but do others? I know we are in conversations with others all the time, and I try to have faith that if there are enough of us, we can make a difference, but sometimes, it’s just hard to imagine. I like to think that all of us “do” mathematics already. Math seems so natural to me, like breathing. Adults and children, in expressing their disdain for mathematics, sometimes don’t see their mathematical actions and thoughts as such. I want to help bring those endeavors to the fore. H: For my students, I want to highlight that there are a myriad of ways to “do” math. If you are thinking, you are a doer of mathematics. If you are discerning, you are a doer of mathematics. If you are making decisions, you are a doer of mathematics. I want to highlight that the Eurocentric curriculum that informed my mathematics education is ONE way of thinking about and exploring mathematics and not the only way. M: Absolutely! When I think of Jazz, soul food, hip hop, the sky hook...the contributions, the inventions of Black people in the face of an oppressed reality are ingenious. And mathematics lives in every one. Yet, what is recognized as mathematical is often Eurocentric, mainstream, and considered the mathematical canon. H: This has me wondering about indigenous ways of knowing; the fisherfolk in Jaffna, Sri Lanka who feed entire villages and know to sustain marine life, the agriculturalists who worked the land for generations and built homes (without engineers) to raise their families. These ways were lost to Tamil folx as they migrated from the NorthEast to the capital city for a formal education that would allow them to participate in the politics of the nation and ensure representation in government. A national politics that was residual of colonization. Rochelle Gutierrez writes about the need for mathematics teachers to have knowledge; content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, knowledge of diverse students, but also POLITICAL knowledge. Math is not neutral and math teachers are not apolitical. M: I wish you could see me finger-snapping right now! Chills...this is the conversation of our day. When has it not been, really? We seem to be in a moment, and these moments have occurred in history, but if we get it right, we could really restore mathematics and its pursuit to what I believe it was meant to be - done in community, as natural as breathing, not a distinct endeavor of its own. Computational and instinctive, written and verbal, visible and not yet manifested. All happening simultaneously, harmonically. For all to partake as needed. I know you well enough to know that you enter into things with great intention, so I would like to ask your “why” about why you agreed to embark on this virtual conference project. What drove that decision and what are your hopes? H: Sam and I met for the first time at OAME 2019 in Ottawa, Canada. There was an instant connection; we share a true love of mathematics and vulnerability in allowing ourselves to be seen. My "awakening" a few summers ago was quite rude (and not at all gradual). I realized that I had not been seeing myself as an Educator of Colour and as a result was permitting a TON of self-harm but also doing a grave injustice to my students. How can a fractured educator teach a whole student? When Sam approached me with the idea of this Virtual Conference and we agreed on the theme of mathematics as a human endeavour, I knew this was my opportunity to co-create a space of learning and model equity and inclusion in a visible way. We need to do this self work and ironically require a community to do it well. The post above is the first keynote blog of the Virtual Conference on Humanizing Mathematics . You can visit the rest of the posts there.

|

My WhyReflecting is good for the soul. Doing so in public is terrifying and exhilarating. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed