|

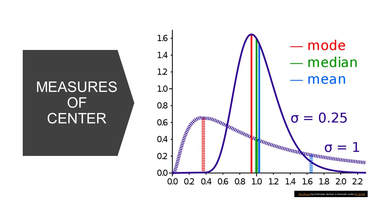

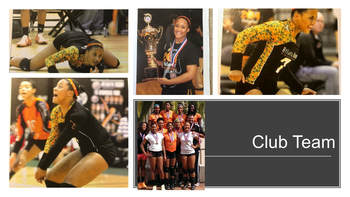

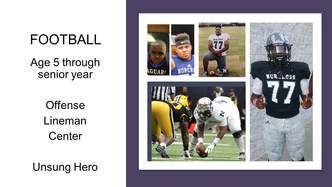

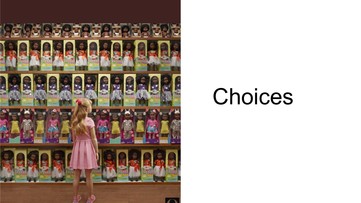

Recently, I was honored to give a keynote address at Twitter Math Camp (TMC). Because some have asked for the speech in written form, I am providing it below, along with some of the slides. Images are either original or licensed under Creative Commons. Let me first begin by thanking Lisa for the introduction, the TMC organizing committee, and our larger Math Twitter Blogosphere (MTBoS) community, for this opportunity to address you. I have received blessings from many who are here, and those who could not be. Second, I would also like to acknowledge that the land we are standing on today once belonged to the indigenous Potawatomi and Haudenosauneega Peoples. I give honor to them and ask their blessing for our time together today. I am not a very familiar name to many, and I would very much like to explain how it is that I ended up here. I begin my twentieth year teaching elementary students, and I have always centered mathematics. I was fortunate enough to have a father who passed on his love for the subject to me. Throughout my teaching career, I have centered mathematics in my students’ lives. Although I teach all the core subjects, I am most commonly known as their math teacher. Although I didn’t have a blog of my own, I followed blogs of math educators, learning from them, and trying out new things with students. Reading Graham Fletcher’s blog led me to so many others, and led me to the concept of MTBoS. Talking to him by phone, he answered my questions and encouraged me to join Twitter and to blog. But, I did not. I felt I had little to say or contribute, and was quite happy watching from the sidelines. Until. Late 2016 was when things changed. I joined Twitter, seeking answers for why the world was the way it was. I mostly lurked in the beginning, occasionally retweeting. I really wanted to know how to do school better for kids who looked like my own kids. As long as I had been teaching, things really hadn’t gotten better for kids of color, and specifically Black kids. I wanted, I needed, answers. And I looked for them on Twitter. Yet, I didn’t see as much as I wanted. I thought it was me: Maybe I didn’t know who to follow, or maybe I just wasn’t on their radar, because surely, those people existed. So when I saw a tweet advertising TMC, it made sense to apply, to seek those answers from the very math community Graham had introduced me to years ago. It was held locally, so I could attend each day and go home each night. I got on the wait list, was selected, and was all set. What I found was interesting. I managed to match faces to Twitter profiles, and many gave me friendly hellos (Hi, Hedge!) but I really knew no one. I admit I was surprised that there were not more educators of color, specifically Black educators in the space. I came during a time when people were talking about diversity, and the lack thereof, and confronting it. It was obvious that this conversation had been brewing for a while. I’d come to TMC with a mission – to find out everything I could about teaching mathematics in a way that honors students of color, in a way that leads to liberation for us all. I thought, surely, TMC would have my answer. In short, I came to learn about combining mathematics with social justice. I am still seeking those answers. From last year until now, I’ve done things I never thought I would do: writing blogs and collaborating with strangers. I am thankful for the examples of Grace Chen and José Vilson, to name a few, who have been centering the discussion of equity in mathematics for years. They each delivered a keynote here in the last two years, and I am here to continue what they, and others, have started. So let’s get started. Measures of Center (or measures of central tendency) have a particular mathematical interpretation. The analysis of a data set, reducing it into one “typical” value, is useful to make judgments about that data and how it is used. As an elementary mathematics teacher, I’ll center the definitions as mean, median and mode. Of course, data sets are often asymmetrical and contain extreme values, which affect its center. Distributions of this sort can sometimes be described as skewed or even biased. But I am advancing that our mathematical definitions are metaphors for many societal realities. The center is often what or who is valued, since it represents the entire data set. Often, by framing this measure of center, much of what is truly important disappears. In our discussion today we will encounter different frames of center. Let’s look at the Sports Center. From a young age, my husband and I felt it was important to expose our children to sports. Teamwork, discipline, a sense of belonging to something bigger than yourself, and physical activity were very important to us, and we wanted this for our kids. They tried everything: ballet, gymnastics, soccer, tennis, basketball, baseball, softball, and swimming, but finally landing on football and volleyball, playing these throughout high school. They each began at age 3, often following each other into said sports. My daughter began volleyball in 6th grade in a recreation league. She decided to get fairly serious about it in 8th grade, and talked us into a travel club team. Once we moved back to our home state, she made the Freshman Team of her high school. Now in volleyball, there are six main positions, and she was a pretty good hitter. The hitter is offense - a front row position, and is the last touch of the ball before going over the net. Optimally, the hitter should be tall and able to clear the net so that the ball is angled downward as it descends. As it turned out, she had a killer serve, and was a powerful hitter by freshman standards. They won their championship pretty easily. In the high school off season, she wanted to again play for a club team. She set a goal for herself to make the Varsity Team the following year, and knew she would have to raise her competitive level. She worked hard, and she made Varsity as a sophomore, which was pretty unheard of, but eventually switched to a defense specialist or libero position, once she realized that she had reached her maximum height of 5’4”. Here is her Varsity Team. Now, I’m going to ask you to notice and wonder here. Although her high school was diverse, volleyball was not. There were 3 Black girls on the team of 14. I was the Team Mom for her 3 years on the team. Do you think that mattered? I suppose I did what I had always done with my children. Because they were my center, I sensed that I would be needed to help navigate the microaggressions that may arise. I received some myself through those years, so I was able to model some strategies and foresee challenges. As a libero, she was now a back row player, tasked with the first touch. In fact, it was her sole responsibility to “dig” balls, preventing them from hitting the floor, no matter how hard or how angled those balls were, often sacrificing her body to keep the ball in play, and get it to the setter. She enjoyed it. It’s often called the toughest position, but it is not one that receives glory. She would never be the one to score a kill or make a block, and would be blamed if the ball ever hit the floor. Here is her Club Team. Again, I ask you to notice and wonder. Yes, I believe that she was far closer to these teammates than those on her school team because her racial identity was affirmed. They entered tournaments in which they were the only Black team, and won. They faced microaggressions here, but they faced them together, and with their families. The “norm” for volleyball in our region was white players. This team would also have 3 years together, winning tournaments, going to Nationals, and playing in the Junior Olympics. My son played as both an offensive and defensive lineman from a young age, but when he got older, he switched to offense as a center. So, similar to my daughter, he had the first touch of the ball. It was his responsibility to snap the ball to the quarterback, enabling others to make plays. Again, the center, although also often called the most important offensive position, is not one of glory. But he was my center. I would watch him first, then the ball later. And the same with my daughter. For me, I was in awe of the precision they both had to have to do their jobs as they watched their teammates score. What a responsibility – and a lesson in humility. As their mom, I centered them in sports. Yes, I paid attention to the game and to the other players, but if I am honest, I always had my kids as the center. My focus wasn’t on the score, the running backs, the hitters. I still saw them, but they weren’t my focus. Why is that important? If I hadn’t centered them, then who would? If I didn’t look for their moments of greatness, who would? If I wasn’t their biggest cheerleader, fan, coach, then who would be? Like his sister, my son made Varsity as a sophomore. Their state championships came before he got there, but they reached the playoffs each year. Many of his teammates went on to Division I scholarships, as did my daughter’s club teammates. My daughter decided not to continue volleyball in college, but my son did decide to become a college athlete. For us, his choice is a practical one. He still gets to continue a sport he loves, and is in an excellent college that offers what he needs and wants: a small campus, small class sizes, and a coaching staff who recognizes his talent, commitment and intelligence. I look forward to another season, and I will be at every game. My husband and I consciously chose to center our children in their Blackness. I know what it feels like to be the only one in a classroom, the only one in the high group. You are torn because you are proud of your accomplishment, but sad to be treated as the exception. After some years, you find the words to match your feelings and you are determined that your children will not experience that. You do everything in your power to give them a firm internal center that can be leaned upon when the teacher doubts their ability. We wanted positive Black role models for them, and sought out a primarily Black professional neighborhood in which everyone knew their neighbors. And for 11 years, we had just that. It was often the case that on any given Saturday morning, we would find our son playing next door with his “best friend” who was like a grandfather to him. Indeed, he and his wife served as surrogate grandparents to them, watching each of them during school hours from birth to school age. Weekends and holidays were often spent with them and other neighbors. We celebrated in each others’ successes. We even vacationed with them. Their preschool and elementary years were spent with primarily Black teachers and among Black children. My daughter played with Black dolls. At the mall, grocery, pediatrician, and everywhere in our community, they were around Black people. This was their center. This was their normal. We never thought about it much, but our children had little in-person involvement with non-Black people. Yet, they were socialized just the same. Every checkout aisle contained magazines with white faces. The television and movies they consumed rarely featured Black children as main characters. Our decision was therefore necessary to counter those influences. It was this immersion that set their foundation for years to come and would steel them from the hurdles I had faced, I hoped. This was fine until work relocated us to another state, and we were faced with attempting to recreate this “normal” in our nation’s capital. It was a challenge, but we settled upon an Eastern suburbia. We ended up in a place that offered the best we could find of both worlds: a track record of demonstrated academic achievement (yes, through test scores, because that was the only measure of which I could go on), among a diversity of students and faculty. My son came to school with me, and we were both in third grade, but in different classes. Watching him navigate among students of different races was hard at times. Finding friends when he was among the few Black kids in the high group was difficult. And, this gregarious child who had never had trouble finding friends before seemed to be floundering. This was his first white teacher as well, my teammate, who never really made a connection with him. The next year, I became the gifted teacher, teaching mathematics to students who qualified through testing. Sam had not been recommended for testing by his previous teacher, but the fourth grade teacher did. He qualified, and in fifth grade, he was my student. I wish I could say he loved being in my class. I know I loved having him. But, there was a certain pressure for him to prove he earned his spot that he never got over. He had made friends through sports, but not school. I hoped for a better middle school experience. My daughter began middle school on her own, and had to prove herself academically as well. Underestimated at first, she was taught by Black and white teachers who genuinely loved her. She formed tight friendships that continue today. Another job change brought us back to the original state. Our once ideal neighborhood had drastically changed in the 3 years we were gone. The recession proved devastating. We chose a different community similar to the one we had just left. But, they discovered that things would not be the same and their choices were no longer ideal. My daughter continued to excel in high school, but would not have any more Black teachers. She kept to herself mostly at school, and found her community among her club volleyball team. Microaggressions from teachers, classmates and school teammates were the new normal. Middle school was tough for my son. Known for academics, it was a particularly harsh place for students of color. His seventh year was the worst. By second semester, his grades had plummeted and he seemed to always be in trouble at school. He was on “that” team known for harming students of color, especially Black males. Being new parents, we did not know this. Our son tried to handle things himself, but nothing worked. For fear of not being believed, he did not tell us when it first happened. Two team meetings later, we came to an agreement. The teachers most responsible for the abuse backed off. But the damage had been done. In high school, my son became a social butterfly, fully embracing his underachiever jock role. Although the school was diverse, the football team was overwhelmingly Black. He had found social comfort again, and was tired of playing the school game. He did just enough to appease his father and I. Both are in college now, out of state, and doing well academically. They survived. I wonder what would it have taken so that they had a good experience throughout. Shortly after I joined the world of Twitter, the movie, Hidden Figures was released. How many of you have seen the movie? Anxiously awaiting it, I viewed it early, in December, shortly after Christmas. Like so many, I was struck by this important mathematical and cultural history that was new to me. I went to Twitter to read all the tweets about how wonderful the movie was, yet there were few. I told myself that this must be because I had viewed the movie in one of the cities that released the film earlier. I wanted to process it with a mathematical lens. I told myself that I would have to wait until the movie was released more widely across the country. Surely then, the MTBoS would weigh in. I have alluded to this a few times on Twitter, and I don’t mean to reduce anyone’s contribution. Please hear me. This is my perception as a person new to MTBoS who was specifically looking for something I felt missing from my teaching. The reaction, in my interpretation, was indeed a reaction to this hidden history. It was a joyous one: we now had proof of the labor of Black women in mathematics and engineering, occurring during the Civil Rights Movement no less. The focus seemed to be on the importance of representation, which, I agree is essential. There were field trips to movie theaters, research projects, and even living museums. Yet, I was looking for something more. What I wanted was for someone to say, “Ah! Math is political!” But that never came. I will try to explain. Hidden Figures is based on the work of Margot Lee Shetterly, who has chronicled a nonfiction account of the stories of Black female mathematicians of the Langley Research Center in Virginia, which would later become NASA. They were called computers, who performed calculations largely by hand. There were 2 groups of computers, of course, since segregation was the law of the land. When the call goes out to recruit a computer specifically for the Space Task Group, an all White, all male group, Katherine Goble Johnson, depicted here as played by Taraji P Henson, is assigned. Here we have the intersection of mathematics and politics. Computing is seen as menial work and is therefore relegated to women. And, there are separate classes of women, which necessitates their segregation. Many of the characters in the movie are composites of others, but there is a significant attention to authenticity I find compelling. I found myself asking: How many other Katherine Johnsons are there that I don’t know about? As Johnson impresses her supervisor, despite the daily micro- and macroaggressions on the job, composite character Al Harrison gives her an insight into his thinking. He says: “Look beyond the numbers. Look around and through them. Answer questions we don’t even know to ask. The math that doesn’t exist. Because without it we’re not going anywhere. And then we’re staying on the ground. We’re not flying into space. We’re not circling the earth and we’re certainly not touching the moon. And in my mind, I’m already there. Are you?” This is such a rich bit of dialogue that begs to be unpacked. Look beyond the numbers. Look around and through them. Answer questions we don’t even know to ask. The math that doesn’t exist. Isn’t this what we want for our students? To not just regurgitate an algorithm, but to imagine, to innovate? Because without it, we’re not going anywhere. An acknowledgement that this innovation is our future. In my mind, I’m already there. Are you? The ultimate challenge is presented. We want our students to see beyond – to visualize in order for this to happen. Yet, there is another layer here that exists, if you choose to decenter systems: To look beyond is to look past our current oppressive systems in school. To look around and through them. To find the math, or the ways to rehumanize education, that doesn’t yet exist. To find a way for students of color to see themselves in our curriculum. To see themselves as capable and innovative. This line really hit me. This is the imagining, isn’t it? In my mind, I am already there. My kids and their kids are receiving a humanizing education that liberates and affirms their racial identity in all its ways. Of what oppressive systems do I speak, you ask? Reading the book Black Stats this year with the MTBoS book club that Annie Perkins started, we became keenly aware that from many viewpoints, Black citizens in this country fare nearly the worst on any measure. Our public schools are mostly Black, Indigenous and Students of Color (BISOC), yet it is those students whose scores are lowest, who are retained at higher rates, who are the least likely to be enrolled in gifted or enrichment classes, and are the most likely to be suspended. I know we have all heard the reasons for this, but, unless you believe that BISOC are inherently less gifted, less capable, and more behaviorally challenged than White students, then you must admit that there is something wrong with this picture. Putting it another way, if you are okay with these statistics, then you are accepting this as your normal, your center. No, it is not a matter of poverty and economics. Study after study show that when compared at equivalent levels of family income, the same patterns exist. The same sad statistics are found in health, the environment, sports, entertainment, justice, lifestyle, the military, money, jobs, politics, and science and technology. It is eye-opening. I encourage to read this text if you have not already. Last year, Grace gave an excellent keynote about the question of mathematics being political. In analyzing this movie, I find a curious juxtaposition of the themes of patriotism vs. oppression. The patriotism is expressed through the seeking of new mathematics, and it is in the backdrop of the oppression of some of those tapped to seek it. The irony is astounding, if you allow yourself to decenter the white norm enough to see it. “We can’t get anywhere without the numbers.” To be more clear, they couldn’t seem to get anywhere without the numbers of Black women. The scene on the left is when the John Glenn and the astronauts are paraded among the NASA employees in a great moment of patriotism. On the right, the very next scene shows Johnson discovering a new coffee pot just for her, reminiscent of separate but equal. Time and time again, we see that Johnson is expected to perform her patriotic duty by doing the math, while that very task is increasingly made difficult - literally hiding some of the information from the calculations she is to check, segregated bathrooms, etc. Did this discussion go into the Hidden Figures units put forth by the mathematics educators community? Was this part not important to discuss with students – how the racist acts of yesterday were overcome, but exist in new forms today? Did you ask any of your students if they could relate? Maybe this does exist in the curriculum. Maybe I missed those conversations. But it’s what I wanted to discuss then, and now. I think our students can handle critical analysis. Don’t they need to be prepared? Our children deserve the truth, and the truth includes our racist past and present. As Dr. Erika Bullock has written, this lack of discussion amounts to figure-hiding. Johnson had to fight to be seen and not hidden. Are you hiding your own students? Or, if you do not teach students of color, are you assuming their absence in mathematics? The movie next goes to the story of Dorothy Vaughn, as portrayed by Octavia Spencer. Vaughn sees that human calculators are being phased out, and notices the IBM coming. Her supervisor, composite character Mrs. Mitchell replies, “You all should be thankful you have jobs at all.” That response also seems familiar: Black people hear often we should be thankful segregation is no longer the law of the land. If we are in private school, we should be thankful, or we should be thankful that we aren’t in “that” class. No regard to the system of inequality that exists, or that segregation still exists. Or isolation, dehumanization, or microaggressions exist. In the next scene, we see Vaughn and her 2 sons walking to the library. They pass protest marchers fighting against their segregated city. Once inside, she is approached by the librarian who quickly asks her to leave because she is in the white section. We should note that she is in the white section to read a book that is not in hers - one on Fortran, which she will need to say ahead of the computer layoffs. Vaughn refuses at first, then is “helped” out by a police officer, but not before she hides the book under her coat. We then see her reading the book, on the back of the segregated bus with her sons, when one asks if she has stolen it. Her reply is classic resistance: she says that as a taxpayer, she pays for the use of the book. The camera then goes to a picture of a colored vs a white fountain. She says, “Separate and equal are two different things. Just ‘cause it’s the way doesn’t make it right.” So much to teach here:

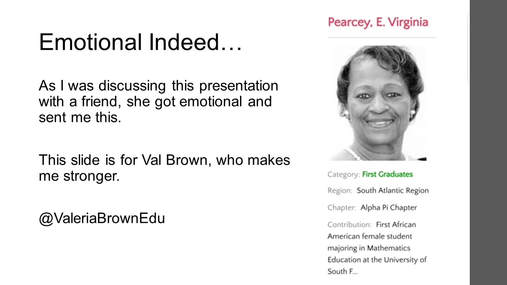

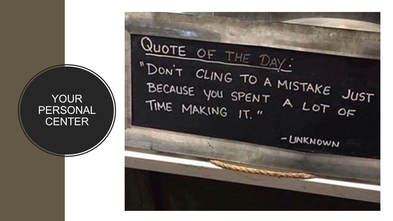

Vaughn goes on to teach herself Fortran, and the Black women she works with, finally earning the supervisor role she has been fighting for. Some quotes that are heard in the background. JFK speaks of the moon. Is racism harder to tackle than travelling to the moon? A poignant quote from MLK. I think we as educators need to really ponder this to see if we believe it. If not, what are we doing? At this point, we learn of the story of Mary Jackson, as played by Janelle Monae. When asked by her supervisor if she would want to be an engineer if she were a white male, she answers with the famous line, “I wouldn’t have to. I’d already be one.” She ends up petitioning the court for permission to attend an extension class only offered at a segregated white high school. She does attend the class, and continues the road to becoming an engineer. She does so by also demonstrating strategic thinking in her exchange with the judge, and resisting the current state of affairs becoming the first Black female engineer at NASA. As Katherine is depended upon more and more, she is frustrated that her calculations are obsolete soon after she submits them. She requests a seat at the table as changes occur to improve her accuracy. Her demands eventually are met, since her work is impeccable. Upon proving her mathematical prowess, she compiles reports of her work, only for a man’s name to be listed as the solo author. She resists by typing both names, and each time is reprimanded for doing so. Toward the movie’s end, she is allowed to list her name along with her supervisor’s. We could speak to students about authorship and the right to original ideas. Is this not important in math class? All 3 of these women were firsts in mathematics, computer science, and engineering. And they didn’t get there by being passive. Each was able to assert themselves to disrupt in ways that they could, although not without consequences. This is the history that must be acknowledged to our students – that even in mathematics, all is not equal. So here’s the thing. It is amazing to me that we can look at the same movie yet see very different things. The reaction and message I interpreted from mtbos was this: There are many mathematicians of color we don’t yet know about. How can we help students discover them so that they see themselves in the mathematics? My response was that PLUS: What would’ve happened if more Black mathematicians were in the Space Task Group? How many brilliant mathematicians were missed? Could we have gotten to the moon faster? Do we hide budding mathematicians today? It’s everywhere in the movie. If you decenter yourself, can you see? Why aren’t we embracing those that look different than ourselves? Isn’t it in our collective best interest? Why can’t we see the gift – the necessity – of sharing the power? If you are standing by while students of color continually lack access to great teaching, then you are modelling compliance for all of your students. Our kids need us to speak up and disrupt or at least interrogate what is going on. Are you waiting for permission? If you are in a school with no students of color, are you interrogating that? Why do you have none? If you teach with no teachers of color, are you interrogating that? You either believe that our education needs all voices or you don’t. You either believe that if some of those voices were no longer hidden figures, we would all benefit, or you don’t. Can we really reach the figurative moon without all of our voices? Or are you teaching your students, your colleagues, your children, that only some of us are smart enough to get there? Representation is important. I was talking to a friend about this talk last week and I mentioned that I saw a connection between Hidden Figures and mathematics education. She got quiet. She admitted being emotional as she pondered her school experience and her family history. She asked me to show you this, because it matters. This is her Nana, who was the first Black female math education student at the University of South Florida. This one is for Val. I know much of this history is new. It is definitely new to me. It is new because it has been hidden. That’s what makes the MTBoS book club so powerful. We chip at these books one by one, so that we can decenter the lies we have been told in our schooling. We need to improve our racial fluency. We are good with the numbers, just not good with each other yet. Lean into your discomfort. Ask yourself what you are feeling. Decenter yourself and listen to those who find themselves at the margins. Imagine their point of view. Decentering self is a lifelong journey, but it must be done for our students and for all of us. To revisit the Harrison quote, like Jackson, we have got to look beyond. Like Vaughn, we have to ask the questions we don’t even know to ask. Like Johnson, we must invent the math that doesn’t exist. Because without it we’re not going anywhere. I don’t want any more dehumanizing mathematics. I reject teaching this way. I imagine all my students seeing themselves without limit in the mathematics. In my mind, I’m already there. Are you?

7 Comments

7/27/2018 11:07:25 pm

Thank you for sharing this with us. I can do better than having a “Hidden Figures,” poster in my room and Ceasar Chavez on my wall. I can trust that my SOC are eager and ready to imagine the mathematics to get there.

Reply

7/28/2018 09:21:50 pm

Marian, thank you for each and every word here. I am so sad and so angry that we white people have gotten this so wrong for so long. Your voice and wisdom is desperately needed. Thank you for sharing it here.!

Reply

Marian Dingle

7/29/2018 07:02:18 pm

Thank you for your kind words, Tamara.

Reply

Rachel Kernodle

7/29/2018 06:31:04 pm

Thank you so much for posting the text of your keynote here. I have read, reread, and am excited to share with my colleagues who could not attend TMC.

Reply

Marian Dingle

7/29/2018 07:00:58 pm

Thank you, Rachel. I’m glad we met and look forward to conversations with you in the future.

Reply

Joy

7/30/2018 01:16:50 pm

I loved this movie. I too learned about this hidden history. I was able to shre this movie with one of my senior statistics classes last year. The class was made up of mostly students of color. It was an experience I will never forget. Many were not aware of this history. We talked about how some things have changed but that we have many changes that still need to happen. Thanks for your post.

Reply

Marian Dingle

7/30/2018 10:03:50 pm

Thank you for reading and recognizing with your students that much of the struggle continues.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

My WhyReflecting is good for the soul. Doing so in public is terrifying and exhilarating. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed